A Rare Cause of Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Jejunal Dieulafoy’s Lesion- Juniper Publishers

Journal of Surgery- JuniperPublishers

One in a thousand people have an acute gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage per year [1]. There are around 300,000 hospitalizations for GI bleeds, costing an estimated $2 billion per year [2-4]. Compared to lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB), upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is associated with a much higher mortality rate, with some studies suggesting a 30-day mortality rate of up to 14% [2,3]. A majority of these UGIB (67 - 80%) are attributed to gastric erosions/ulcers 6,17,18. However, of this morbid group of bleeds, a rare (1% or less), yet more serious cause is a Dieulafoy’s lesion (DFL). DFL, is an obscure type of bleeding that can cause life threatening hemorrhages with a mortality rate ranging from 28-67% [5,6].

DFL was first described by MT Gallard [7] in 1884 as a type of aneurysm and later clarified by P. G. Dieulafoy in 1898 who believed this was an early stage of ulceration [7-9]. DFL’s are a collection of large tortuous arterioles of the gastrointestinal vessels. These are often compared to aneurysms, however, DFL’s are caused by genetic malformations rather than degeneration. While the exact mechanism of rupture and subsequent hemorrhage is still poorly understood, several studies have suggested mucosal erosion and ischemic injury, related to aging and/or cardiovascular disease, as possible causes [10]. DFLs are predominantly seen in elderly patients (mean age 69.7 years) though they can be seen in younger patients as well. A vast majority of patients also will have underlying comorbidities such as renal failure, diabetes, or coronary artery disease. Additionally, there have been a few isolated cases associated with chronic immunosuppression whether from underlying malignancies or medication induced [11].

More than 70% of these rare lesions are found in the stomach, usually near the lesser curvature. The discovery of extragastric DFL’s are infrequent, with the duodenum (14%) and colon (5%) being the most common locations [12-14]. The most unusual site is the jejunum, which accounts for 1% of all DFL’s [12-14]. Historically, there have been a few case reports worldwide of jejunal DFL’s, however, of these reported cases, the lesions were found by advanced imaging (CT angiogram or Bleeding scan). We present a case of a jejunal DFL that was unable to be found by advanced imaging but was diagnosed on push enteroscopy.

Assessment

The patient was a 79-year-old African American female with a known history of end stage renal disease and large granular lymphocytic leukemia. Over the course of 8 months, the patient had 3 admissions for gastrointestinal bleeds. She received a total of 16 units of blood with 4 EGDs, 2 colonoscopies, 1 bleeding scan and 1 CT angiogram. Of the listed procedures performed, all were negative for active bleeding and there was no solid evidence of a bleeding source. She was presumed to have bled twice from erosive gastritis and the most recent admission was from an unknown etiology. An outpatient small bowel capsule study was done after these admissions showing no findings.

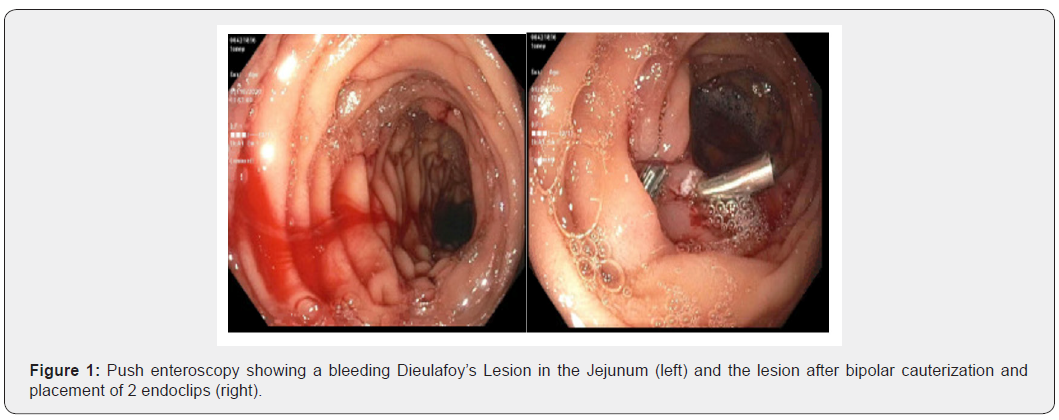

She subsequently presented to the ER 24 days after her most recent admission for melena and orthostasis, where she was found to have a hemoglobin of 4.4 g/dL (previous hemoglobin was 10.2 g/dL). EGD and colonoscopy did not show any findings or source of bleeding. The patient continued to have melena and required 8 units of blood. A CT angiogram and bleeding scan were again inconclusive. A push enteroscopy was performed on day 6 of admission, showing an actively oozing area in the jejunum with no surrounding ulceration or malformations (Figure 1). Bipolar cauterization and 2 hemoclips were placed ceasing the actively bleeding Dieulafoy’s lesion. The patient’s hemoglobin stabilized, and the melena resolved 1 day after the enteroscopy.

Management

Our patient had a history of large granulocytic lymphocytic leukemia (LGL) and end stage renal disease. Though the usual course of LGL presents with neutropenia and anemia, thrombocytopenia can be seen in up to 20% of cases [15]. Thrombocytopenia combined with immunosuppression from underlying malignancy and ESRD put this patient at an increased risk of developing hemorrhagic complications such as DFLs. On multiple admissions, our patient was found to pancytopenia, likely as a result of her bleeding and immunosuppression. To date, there have been a few case reports citing immunosuppression, immunotherapy, and thrombocytopenia all being associated with GI bleeds due to a DFL [16,17]. While the mechanism is not yet established, it is thought to be related to impaired tissue remodeling and repair.

The current endoscopic modalities to manage a DFL include mechanical treatment (with endoclips or band ligators), injection therapy (with diluted epinephrine), thermal coagulation therapy, or in some cases, a combination of different modalities. Two controlled trials suggested that mechanical hemostasis with endoclips can control acute bleeding and may reduce recurrent bleeds compared to injection therapy alone [18]. There have been no studies comparing the efficacy of thermal coagulation alone or in combination with other methods. A second trial comparing endoclips to injection therapy with epinephrine showed equal rates of initial hemostasis but significantly lower rates of rebreeding in the endoclip arm (0%) vs epinephrine arm (35%) [19].

Post endoscopic management depends on whether the patient is at high risk or low risk for rebleeding. One method used to calculate risk of recurrence is the Glasgow - Blatchford bleeding score (GBS score). A GBS score of 0-1 is considered low risk for rebleeding, and in this case the patient may be discharged from inpatient care with plans for outpatient endoscopic intervention. Inpatient treatment is recommended for patients with GBS scores of 2 or greater [20]. The rate of recurrence of bleed for a Dieulafoy’s lesion ranges from 9-40% [21]. There is a higher rate of recurrence with endoscopic monotherapy compared to combined endoscopic interventions [22]. The rate of rebleeding is not associated with gender or location of DFL or past medical history [23]. Inpatient treatment recommendation is to treat with IV pantoprazole for 72 hours in order to keep gastric pH above 6 in order to maintain intact coagulation process, followed by oral pantoprazole therapy. While mortality is lowest in patients with no significant medical history or comorbidities, overall longterm prognosis of a DFL is favorable once primary hemostasis is achieved [24]. Following push enteroscopy our patient did well without any further complications or signs of rebleeding [25-30].

Conflict of Interest

All authors have read and approved the submission of this manuscript. The manuscript has not been published and is not being considered for publication elsewhere, in whole or in part. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper

Comments

Post a Comment